Our Mind-Body Connection

I typed up my behavioral neuroscience notes from college and tried to make the more entertaining. This is more for housekeeping & testing out my blog hosting software than content but… enjoy!

tldr at the bottom

Hormones: Brain-Body Communication

Up to this point, we know that neurons communicate information by passing action potentials via neurotransmitters from synapse to nearby dendrites (If you can understand that sentence, you are on top of this material!). But there are other ways to pass information everywhere. Hormones are things that your body releases into your blood stream to send transmitters all over your body. This is done by neurosecretory neurons: neurons that, instead of having synapses connected to other neurons, have synapses connected directed to the blood stream that release hormones. Endocrine cells release hormones into the bloodstream, and Exocrine cells release hormones “outside the body” to places like the skin and gut.

(Disclaimer: Ignore the following list of hormones until later when we start referencing hormones by group and we have a better understanding of what each hormone does. Just understand the general groupings)

There are multiple kinds of hormones:

- Protein/Peptide hormones are strings of amino acids, examples include ACTH, FSH, Growth Hormone, Insulin, Oxytocin. Peptide hormones can’t pass through the oil cell membrane, so they rely on a second messenger such has cAMP or cGMP to convey their message inside the cell.

- Amine Hormones include Epinephrine, Norepinephrine (a neurotransmitter AND hormone), thyroid hormone, and melatonin.

- Steroid hormones include gonadal hormones like estrogen and progestogen and adrenal hormones like cortisol. Unlike peptides, steroid hormones can pass through the cell membrane and bind to receptors inside the cell. Because of this, they can act as a transcription factor by having influence on gene expression. This makes their effects slow but long-lasting.

Hormones are regulated different negative feedback loops, meaning that the more of a hormone is present, the less it is produced. A system like this can be built with Autocrine Feedback, where the hormone itself inhibits the production of more hormone, or Target Cell Feedback, where a secondary cell overproduced because of the presence of a hormone inhibits the production of more hormone.

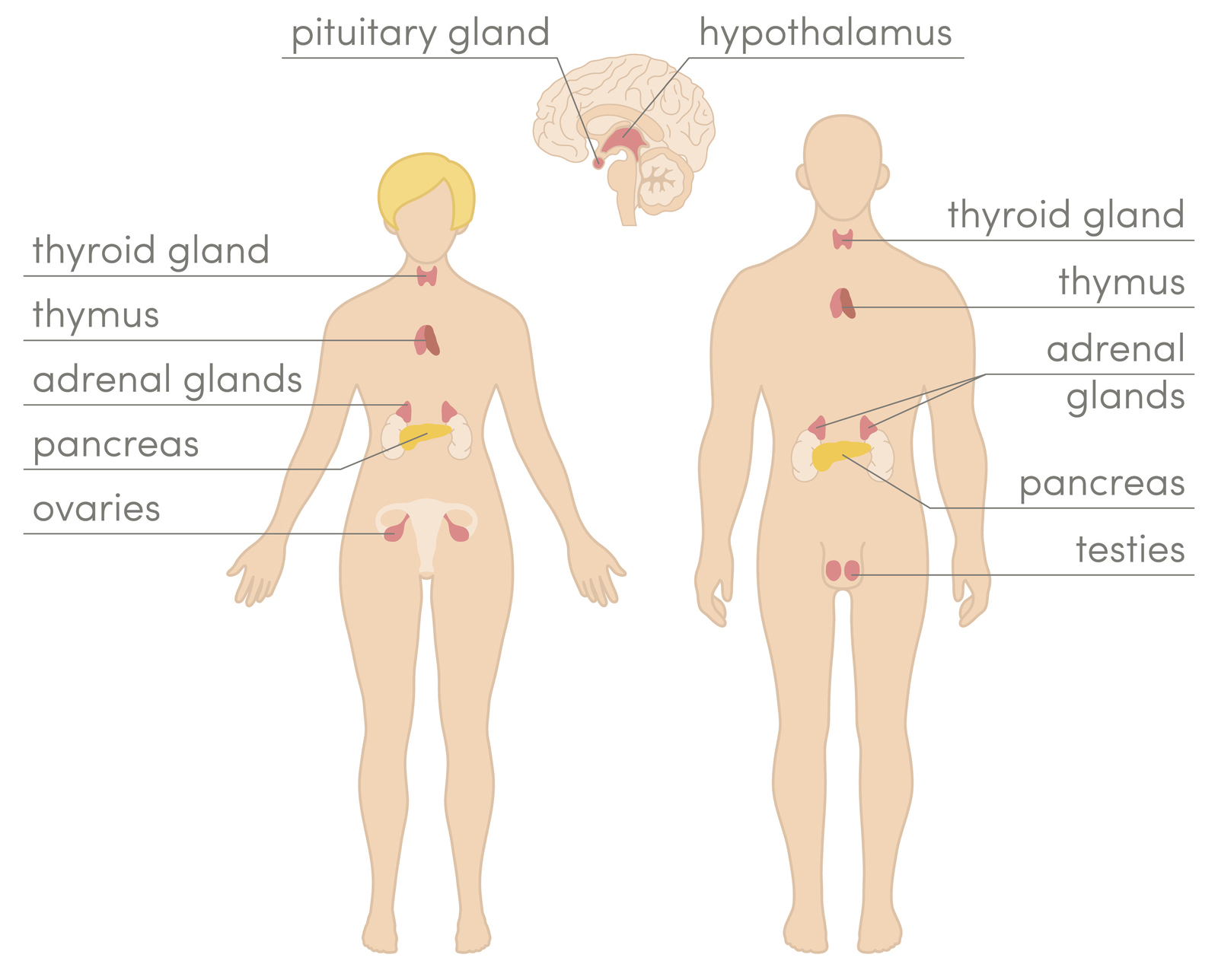

The ultimate controller of all feedback loops is the Hypothalamus. The hypothalamus controls most of the endocrine system and it’s main glands: pituitary, pineal, pancreas, and gonads. Each gland has its own set of hormones it can release.

Glands

The Pituitary Gland is directed below the Hypothalamus and is actually split into two different glands: Posterior (back) Pituitary and Anterior (front) Pituitary.

The Posterior Pituitary is connected directly to the Hypothalamus through long neurons/axons called pituitary stalks. It releases two hormones: Vasopressin and Oxytocin. Vasopressin acts on the kidney to conserve/regulate water in the blood by inhibiting the formation of urine. Oxytocin in females is released during childbirth to stimulate contractions and triggers milk letdown during nursing. Interestingly, it is released when hearing a baby cry and during orgasm, so it is theorized to promote bonding… sometimes it is called the “Love Hormone.” Outside of these instances, research also shows the Posterior Pituitary is important for bonding: Oxytocin promotes pair-bonds in females, and Vasopressin promotes pair-bonds in males.

The Anterior Pituitary is connected to the Hypothalamus through a system called portal circulation, where neurons from Hypothalamus dump compounds into blood stream that leads directly to the Anterior Pituitary. It releases Prolactin, which stimulates lactation, and Growth Hormone (GH) which is mostly released during sleep and influences growth. In addition to these hormones, the Anterior Posterior releases four trophic hormones, or hormones that affect other endocrine glands. These are:

- ACTH: Controls the production/release of steroid hormones in adrenal cortex

- Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH): controls thyroid hormones

- Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH): stimulates the production of either sperm or egg follicles

- Luteinizing Hormone (LH): Stimulates either testosterone from testes or eggs follicles to form

Gonadal-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) is dumped into the blood by the Hypothalamus and is what causes the Anterior Pituitary to release LH and FSH. Oral birth control works by blocking the release of GnRH, which prevents LH and FSH from being released, which prevents an egg from entering the ovaries.

The Adrenal Gland is located on top of each kidney. In response to ACTH releases adrenocorticoids (hormones released by adrenal gland). Glucocorticoids increase glucose in the bloodstream. Mineralocorticoids help retain sodium and water in the blood. Sex steroids, as the name suggests, increase energy and sexual drives.

The Pineal Gland is a tiny gland at the top of the brainstem. It releases melatonin at night, an amine hormone the regulates sleep.

The Pancreas sits right behind the stomach and is actually controlled by the Vagas Nerve, not the Pituitary/Hypothalamus. It releases two competing hormones: Insulin, which decreases blood sugar in anticipation of a meal, and Glucagon which increases blood sugar afterwards.

Sex and the Brain

This is not a sex-ed recap, but rather a quick look at the effects of sex hormones on the nervous system and body. Despite the potential, talking about sex in behavioral neuroscience is not as sexy as one would hope.

First, sex is determined by the Sex-Determining-Region-of-the-Y-chromosome (SRY), which causes cells in the medulla to development into testes and promote male development. In absence of a Y chromosome and SRY, cells in the cortex will become ovaries instead.

There are some neurological differences between sex as well. Male brains have motor neurons dedicated to ejaculation while female brains have motor neurons dedicated to contraction. The hypothalamus is also shown to statistically different between males and females.

Estrogen and Testosterone are crucial to sexual behavior and organization. Developing testes produces testosterone and anti-mulleran hormone (AMH) which in absence of allows the created of fallopian tubes. A lack of testosterone abolishes male copulating behavior, but a large influx does not increase sexual arousal or performance; a very little is enough, more is not better. Estrogen production leads to ovulation as well as Lordosis, or as a neuroscience professor explained to me, the “head down, ass up” response.

On sex itself: Human sexual response consists of four stages: excitement, plateau, orgasm, resolution. Men have only one site of erection, while women have many (breasts, nipples, clitoris, etc.). Males generally have a single brief orgasm followed by a refractory period lasting minutes to hours, while women can have several orgasms in a row. Sexual arousal is mediated by the parasympathetic system, and ejaculation is mediated by the sympathetic.

Homeostasis: How we keep our internal environment stable

Homeostasis is the active process of maintain a relatively stable, balanced, internal environment. The reason why this is important is that many internal processes require a very specific setting to work properly. For example, chemical reactions run faster at higher temperatures. So if you’re body were to decrease by just 10 degrees, chemical reactions would happen 2 – 3 times slower than usual (Called Q10). This would completely destroy the flow of most of your chemical processes.

Homeostasis works on negative feedback. Negative Feedback works by having a stronger response the farther the current state is away from a set point, or optimal value. Think of a thermostat—the farther away from the set point it’s supposed to be at, the colder/warmer it will make it’s output to help push room temperature to the correct value. In humans, this set point is whatever is optimal for our body, for example 98.6*F, and our body works harder to move towards this set point the farther away the outside temperature is to this value. The three most common set points our body fixates on is salt concentration, water volume, and temperature. While all three use negative feedback, we are going to talk more in-depth about temperature.

Temperature Homeostasis

Endotherms are animals (mammals and birds) that can regulate their body temperature by generating heat internally. Ectotherms (like snakes) don’t do this, instead relying on external heat like sun to maintain body temperature.

Most chemical energy used by muscles—around 80%— is actually lost as heat. While this may seem like a waste, this excess energy is used to increase our body temperature, and is the reason why we get hotter as we exercise, or why we shiver when we are cold—increasing muscular activity increases our body temperature. 1 calorie of food can raise the temperature of 1L of water by 1*C.

Smaller things have a larger surface-to-volume ratio, meaning that there is a lot more surface area in comparison to how much volume the object has. Since heat is dissipated across the body surface, small things lose heat more quickly than large things, and therefore need to eat more food-per-body-weight than larger animals. This means that canaries have to eat much more per body weight than humans, despite being much smaller and with energy output being held equal.

Motor System: How we Move

There are three kinds of muscle: cardiac muscle found in the heart, smooth muscle found in the autonomic system, and striated muscle found everywhere else. Since striated muscle is the one we have voluntary control over, we are going to talk about this kind exclusively.

Muscles are made up of thousands of muscle fibers, a long cell with many nuclei. Each muscle fiber is connected to a single motor neuron. Motor neurons release ACH onto muscle fibers causing excitatory contractions. While muscle fibers only connect to one motor neuron, motor neurons can connect to many muscle fibers, between 3 and 30. A motor unit refers to a motor neuron and the muscle fibers it is connected to.

Muscle tension (the strain you feel when you lift something heavy) is increased by recruitment of increasing numbers of motor units. Weak stimulus activates small (low threshold) motor neurons found in slow-twitch muscles. Slow-twitch muscles use oxygen and are good for long distances. Strong stimulation activates large (high threshold) motoneurons found in fast-twitch muscles. Fast-twitch muscles are anaerobic and are good for sprinting but get tired easily.

The motor neuron receives input from several places:

- Sensory neurons to make simple reflexes

- Spinal cord neurons that are involved in pattern generators (walking, chewing, etc.)

- Pyramidal System carrying brain signals that initiate activity

- Extrapyramidal System carrying brain signals that modulate activity

The first bullet, sensory neurons, represent an unconscious quick response to stimuli. When a sensory neuron detects something really bad, such as our hand on a hot stove, the signal doesn’t go to the brain for a decision—it would take too long. Instead, when it hits the spinal cord it is immediately sent to the relevant motor neurons. This is why if you touch something hot, your hand jerks away seemingly before you even register it is hot. This reflex system helps you minimize as much avoidable pain/damage as possible.

The second bullet, spinal cord neurons, represent an unconscious activation of motor neurons. This motor system is sometimes called muscle memory. It would be overwhelming to have to remember how to walk, or chew, or run, or ride a bike, every time you needed to (have you ever played QWOP? You have no idea how your to control the muscles in your legs correctly to walk). This system allows your brain to free itself from having to remember everything involved in these activities so it can focus on other, more important things.

The third and fourth bullets are best understood in context of how the brain processes and creates motor stimuli. There are two motor circuit paths: simple & fine movement generation, and complex action generation.

Simple & fine motor movements are generated in the basal ganglia and the primary motor cortex. Much like the primary sensory cortex, the primary motor cortex (M1) contains a motor homunculus: a representation of the body in terms of how much dexterity the body part necessitates. Hands, mouth, and tongue are the three largest areas of M1. M1 sends signals down the pyramidal system of neurons, which have large diameter axons (meaning they are fast conducting) and initiate movements; their name arises from the pyramidal shape of the white matter tracts the neurons travel down. While there isn’t a 1-to-1 representation of M1 neurons and particular muscles/movements, there is quite a strong correlation. The Basal Ganglia is a group of brain structures that each contain a motor homunculus as well. It is mostly responsible for modulating activities initiated by M1.

Complex actions are generated in the cerebellum and supplementary motor area. The Cerebellum is a complex portion of the brain that receives input from both sensory and motor systems, allowing for the feedback control of movement. This feedback is crucial for activities like balance. This modulation is sent down the extrapyramidal system of neurons to the muscles. The supplementary motor area (SMA) is active during mental rehearsal, or preparation of skilled movements or planned actions.

Motor Disorders

As strange as it sounds, oftentimes the biggest breakthroughs in neuroscience and psychology happen because of disease and disorders. The brain is such a black box, that we only really learn what a certain part of the brain does once someone has that part of the brain removed or injured. This is the case in a majority of neuroscience knowledge. Because of this, here are a few examples of disorders and diseases that effect the motor system.

A stroke in M1 causes spasticity in movement, and fine motor control is often lost completely. A stroke in SMA, or areas around M1, cause an inability to plan actions of perform complex acts. Sometimes event simple task performance is inhibited.

Parkinson’s Disease is a degeneration of dopamine cells in the substantia nigra, a part of the Basal Ganglia. This leads to a resting tremor and a difficulty initiating movement due to the lack of basal ganglia modulation to movement signals. Huntington’s Disease, which begins showing signs around 40 years old, is a degeneration of the Basal Ganglia in which inhibition of movement is difficult, leading to excessive movements.

Damage to the cerebellum leads to intention tremors, due to overshooting/overcorrecting movements. Damage can also lead to loss of balance and coordination.

tl,dr;

- Our brain’s hypothalamus, communicates with other parts of the body through hormones that travel from the brain through the bloodstream

- Our bodies regulates important metrics like hunger, temperature, water volume (and potentially love) through negative feedback

- M1, Basal Ganglia, Cerebellum, nearby brain areas all work together to plan, initiate, and modulate signals to muscles units for finer control