Our Five (7) Senses

I typed up my behavioral neuroscience notes from college and tried to make the more entertaining. This is more for housekeeping & testing out my blog hosting software than content but… enjoy!

tldr at the bottom

Today we’ll be covering all our senses; understanding how a property of the outside world gets translated and enters our internal neurological world.

Touch and Pain: How the Brain processes physical sensations

Sensations to Brain Signals

Before we can talk about our senses, we need to answer the glaring question: “How does a physical sense turn into something the brain can understand?” This is done through transduction, the process of converting energy/signal into an electrical signal that can travel through the nervous system to the brain. In essence, transmuting a stimulation into an action potential.

This is done by specialized cells that respond to outside stimulus by opening or closing ion channels. As we learned previously, this is how action potentials are created. Metabotropic Transduction is when an outside molecule, such as a smell molecule or a photon, binds to a receptor, releasing a G protein and opening ion channels. Ionotropic Transduction is when outside energy, such as heat or electricity, interacts with the receptor and opens the channel directly.

In both Metabotropic and Ionotropic Transduction, the larger the stimulus, the larger the response. The intensity of a response can be noted in several ways—either the neuron will fire multiple times, many neighboring neurons will fire at the same time, or the brain will interpret the range fractionation of the neuron. Range Fractionation is based on the idea that, while every neuron is “all-or-none” and therefore cannot demonstrate intensity in a single firing, different neurons will have different threshold for firing—a neuron with a high threshold will indicated a high intensity. Neurons that respond quickly to outside stimuli are called phasic, and those that are slow to respond are called tonic.

Another important concept to understand is Adaption: the progressive loss of response to a maintained stimulus. Adaption is the reason that you don’t feel your clothes against your skin all the time—your body simple stops responding to such a consistent feeling. Another interesting effect of stimulus is that when a neuron fires due to a stimulus, it inhibits the surrounding area. This makes the neurons signal even more pronounced, and makes sure that the neighboring neurons only fire if there is an even stronger stimulus against them.

Some cells, called Polymodal Cells, respond to more than one sense. Synesthesia is when stimulus from one sense creates sensation in another—like seeing color with music.

We will explore how each sense uses transduction and how the brain processes each sense individually very soon—but first we ware going to talk about somatosensation: signals related to touch, proprioception, and pain.

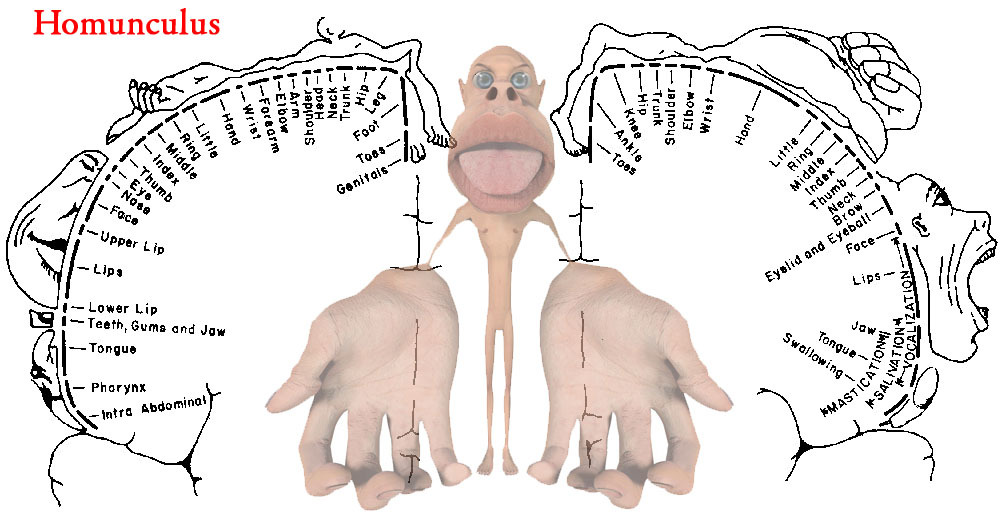

All somatosensory signals are sent up the spinal cord to our brain and mapped onto a 2-D sheet of grey matter in our primary sensory cortex. More sensitive areas of the body have more sense receptors and therefore take up a larger part of the brain. The Homunculus is a terrifying personification of how our brain interprets somatosensation—you can see that our hands, feet, and lips are huge emphasis and our back has very little.

If a body part or the nerves connected the body part to the brain are removed, the brain region associated with that body part will shrink. Neighboring sensory brain areas will begin expanding into this freed up space, given these growing regions more refined sense interpretation. The brain’s ability to change is called Cortical Plasticity.

Phantom Limb is the phenomena in which a person feels like their missing body part is actually there – this is due to the cortical area previously associated with the body part is being stimulated the encroaching cortical regions, but the brain is still attributing it to the old body part.

Somatosensory Signals

Action Potential

Touch is (obviously) the sensation you feel when something applies pressure to your skin. First, think of how cool it is that by pressing on your skin, you are creating action potentials in touch receptors. You have four different touch receptors that serve different purposes:

- Deep, large, and phasic receptors (Pacinian Corpuscle) that communicate vibration and heavy pressure

- Deep, large, and tonic receptors (Ruffini’s Endings) that communicate stretching

- Shallow, small, and phasic receptors (Meissner’s Corpuscle) that communicate texture

- Shallow, small, and tonic receptors (Merkel’s Disc) that communicate light and constant pressure

Proprioception is the sensation of where your limbs even when you can’t actually see them—it’s how your muscle’s “feel”. Golgi tendon organs measure muscle tension/contraction and muscle spindles measure length and change. Limb position is compared in the brain to the limb’s neutral position, which is set by Gamma motor fibers.

Pain, according to the International Association for the Study of Pain, is defined as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage.” Pain and temperature are detected by nociceptors, free nerve endings, and there are three types:

- TRPV1 receptors detect painful heat and capsaicin, the chemical that makes food spicy, and respond slowly

- TRP2 receptors detect quick sharp pains that cause immediate reactions

- CMR1 detect cold and respond slowly

Nociceptors respond to the chemicals released by tissue damage. The dull, aching pain of TRPV1 and CMR1 receptors travel up slow, unmyelinated C fibers. The sharp pain of TRP2 receptors travel up large myelinated A-delta fibers.

Pain inhibition is our brains ability to block incoming pain signals. As pain signals travel up the spinal cord and enters the brain, they pass through Periaqueductal Grey Matter (PAG), which is (potentially) brain area responsible for pain inhibition due to PAG being rich in opiate receptors. As the pain signal passes through PAG, the opiate receptors release endorphins, which in turn activates the release of 5-HT to spinal cord nerves, inhibiting/blocking the incoming action potentials.

Many pain relief treatments use this opioid effect to reduce pain. Rubbing wounds/bruises helps by sending more pain signal through PAG, increases the endorphin response. Acupuncture and TENS both also work by inducing a larger endorphin response due to increasing pain slightly. Because tissue inflammation/damage is what causes nociceptors to fire, anti-inflammatory agents can also help reduce pain.

The Ear: How Hearing & Balancing Work

Disclaimer: Understanding how the ear works is really hard without a anatomical vocabulary. This is because the ear has so many tiny parts are just a bunch of weird shapes. Ears are weird. There are a lot of parts to the ear, so I have narrowed it down just enough for us to understand how hearing works without being overwhelmed by vocab. Hopefully.

Hearing

Before we talk about hearing, we have to talk about sound. Sound travels in waves at a frequency, which is cycles per second—how many times the waves goes up in down in a second. The goal of the ear (and hearing) is to capture these frequencies, from a bunch of different sources, and translate them into action potentials so our brain can interpret them.

When a sound passes enters your ear, it goes through its three parts: the outer ear, middle ear, and inner ear. The outer ear is what most people who considered the whole ear—it is the only visible part. It is shaped so strangely because this shape helps to collect and filter sounds, which is important for sound localization, figuring out where sounds originated. One example of sound localization is how your auditory cortex understands that while it may hear a sound each from every direction, a sound is loudest in the direction it is truly in.

The sound then travels down your ear canal and hits your ear drum, a membrane covering the entrance to the middle ear. The ear drum vibrates differently depending on the frequency of the incoming sound. This vibration causes 3 small bones, called ossicles, to tap against the entrance of the inner ear at the same rate… it’s almost like Morse Code.

The inner ear is made of the cochlea and the semicircular canals. The cochlea is a swirly shaped structure that the ossicles are tapping against. Inside the cochlea are series of canals lined membranes, which are filled with a K+ rich liquid called endolymph. Inside the cochlea’s middle canal is the organ of corti, where hearing’s transduction takes place.

The Organ of Corti is a tiny structure with rows of hairs called stereocilia, with 12,00 hairs on the outside and the 3,500 inside. The bending of the stereocilia one way causes connected K+ channels to open, allowing the K+ from the endolymph to flood in a depolarize the hair neuron. Bending the hair the other way causes the K+ channels to close, polarizing the hair neuron. This depolarization activates Ca++ channels, which in turn releases glutamate down the auditory nerve, a nerve leading from the inner ear to the brain made up of 35 – 50,000 nerve fibers. Each inner hair cell is connected to approximately 20 different neuron dendrites. In this way, frequency is converted in an action potential.

The auditory cortex, the final destination of the auditory nerve, is quite similar to the somatosensory cortex as discussed previously. We even have a surface mapping sounds—a tonotopic arrangement.

While being far less in number, the inner hair cells are the ones literally responsible for hearing—the outer hair cells simple help to amplify sounds that enter the cochlea. Frequency is also determined by the outer hair cells, as high frequencies stimulate hairs near the base of the cochlea while low frequencies stimulate hairs much farther back. When you hear a loud noise or listen to loud music, hair cells start to die—and loss of hair cells is permanent!

If you lose enough hair cells, you can go deaf or become hard of hearing. Cochlear implants help fight deafness by stimulating the auditory nerve in multiple (6 -32) places, providing the user with more tone frequencies to utilize.

Balance

Hearing and balance were grouped together because both senses are found in the inner ear. While hearing is centered around the cochlea, balance is found in the semi-circular canals. The semicircular canals are three paired canals that sit are 90 degrees to each other, corresponding to all three dimensions. Each canal has hair cells in pockets of space filled with a gelatinous mass called cupulla. Just like hair cells in the ear, these hair cells bend as the liquid around the moves, causing K+ channels to open. It should be noted that ear hairs do not fire the action potentials themselves, they open gates that allow secondary cells to fire. These hair cells are connected to cranial nerve VIII, which is made up of 20,000 cells, which leads into the brainstem.

How to taste a taste, or smell a smell

Taste

Gustation is the fancy word for taste. Taste is typically broken down into 5 flavors, each flavor loosely correlating with a specific ion channel opening:

- Salty is due to Na+ channels (salt!)

- Sour is due to K+ channels

- Sweet due TR1 and TR2 channels

- Bitter (evolved to fight poisons) due to ~30 specialized TR2 channels

- Umami due to 2nd messenger responses to certain compounds

These flavors are sensed by the 6 – 10k taste buds we have on our tongue. Taste buds have a 6-day lifespan and have about 100 receptors per taste bud that all focus on one of the above flavors. Taste buds are different from other sensory cells we have looked at so far as the taste buds themselves fire action potentials to the connected receptors. When an action potential is created through transduction, the impulse travels up cranial nerves VII, IX, and X to the thalamus and then to the taste region of the cortex.

Smell

Olfaction is the fancy word for smell. Smell is sensed by thousands of odorant receptors. Odorant Receptors are chemically sensing receptors inside the nose that have many proteins that bind to very specific odorant molecules (smells). This binding activates cAMP—recall this is a second messenger protein—which in turn opens Na+ channels and causes an action potential.

When we breath in, air rushed over our olfactory epithelium, a 2cm^2 region within our nasal cavity where all our odorant receptors are located. Each breath exposes our odorant receptors to a large variety of chemicals/smells, causing a large variety of action potentials to fire. All these action potentials are consolidated by the Olfactory Bulb, a region right above our nasal cavity.

Unlike other senses, smell signals travel to several interesting places prior to the Thalamus. They travel to the Amygdala, center of emotion, as well as the Hypothalamus, center of hormones. This is why smells have a particularly strong association with specific emotions, feelings, states of mind, and memories.

Another interesting thing to note about smell – other animals have a pronounced vomeronasal organ (VNO) on the olfactory epithelium which detects pheromones. Pheromones are chemicals released by nearby animals to subconsciously communicate mood. It is still an open debate whether humans have a VNO or if we can detect pheromones.

How do we See Things?

The visual system is so important, and so complicated, that I’ve broken it into two sections: how the eyes transform light into brain signals, and how our brains interpret those brain signals. Get ready for a crazy ride.

The Eye: How we See Things

The colorful part of your eye is called the iris. When light first enters the eye, it passes through the donut hole in the middle of your iris called the pupil- which really is a hole leading inside your eye. Light then passes through your cornea and lens. Your lens controls your focus—when you relax the muscles around eye your lens flattens, allowing you to focus on distant objects. The lens also inverts the incoming lights so that the image that hits the back of your eye is upside down. All vertebrate eyes invert the incoming light in this way.

The light then hits the retina in the back of the eye, where the light is changed into action potentials by vision cells and sent down the optic nerve. But changing light into electric impulses, as you can imagine, is a very involved process.

A quick not about eye movement—our eyes saccade, or jump, 3-4 times a second. Vision is not a continuous movement, but rather a series of ¼ second glimpses. Watch someone look from left to right, their eyes will make a series of short jumps! We can only move our eyes smoothly when following when tracking a moving object.

The Retina

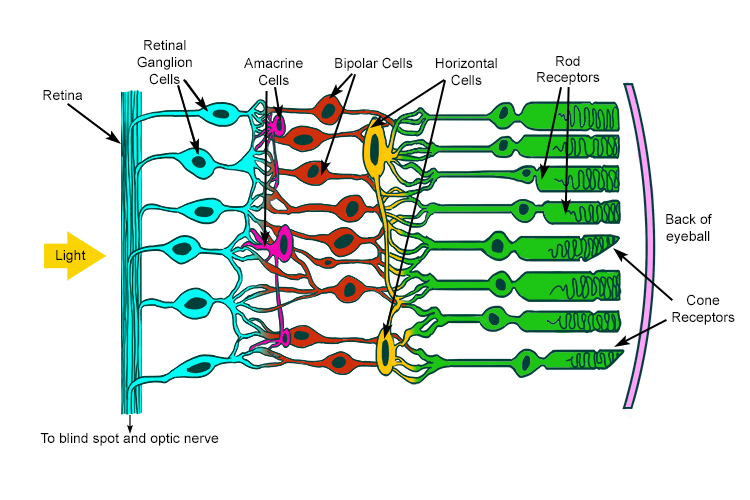

The basic anatomy and order of the retina, for reference later, is:

- Rods/Cones

- Bipolar Cells

- Ganglion Cells

- Optic Nerve

We will slowly walk through each of these layers, but make sure you have a clear picture in your head about all the retina structures as you go along. What you should also know before you begin is that despite being the 3rd layer of vision cells, the ganglion cells are the vision cells that actually fire action potentials.

The first thing light hits when it reaches the back of the eye, and before it reaches the first layer of vision cells, is the pigmental epithelium. This is a thin layer of cells that absorbs unused light.

At the center of the retina is the fovea. The fovea is a part of the center that pushes away all other layers (like the pigmental epithelium) so cone cells can have direct access to light, unimpeded by blood vessels that typically obscure incoming light. The fovea cones are densely packed, giving the Fovea very high visual resolution—this is why your vision is best when you look straight at something.

Another reason that vision in the fovea is so sharp, and it drops off as we move away from center, it that the cones, bipolar cells, and ganglion cells are hooked up to each other in nearly a 1 to 1 to 1 ratio. With a 1 to 1 to 1 ratio, any small change in the visual field detected by a single cone cell will be communicated to the brain, while a larger ration would be this change would be mixed in with other signals being processed.

We have about 125 million photoreceptors in our retina, with nearly 100 million of those being rods and the rest being cones. Despite having over 100 million photoreceptors, all these inputs have to be compressed down to fit into 1 million ganglion cells. This difference in magnitude is the reason why having a 1 to 1 to 1 ratio in the fovea is really impressive and important, and why our vision on the peripheries drops off considerably as we move away from the center of the eye.

We can typically see between 400 – 700 nm, which means we can anything smaller than that we can’t see fine details. The term 20/20 is an ophthalmology (eye doctor) term stating how acute your vision is in comparison to normal. If you have 20/40 vision, that means you see at 20 feet as most people see at 40 feet.

The Retina is also home to the Optic Disc, where both blood vessels and ganglion cell axons can enter/leave the eye. While blood flow and neural connectivity are important, this comes at the cost of having a portion of the retina with no photoreceptors. This creates a blind spot, a blank spot in our visual field. You don’t notice this blind spot because your brain fills in the empty space with what it guesses is around it! There are plenty of quick tests you can find online that help you find your blind spot, it’s pretty awesome.

Photoreceptors & Phototransduction

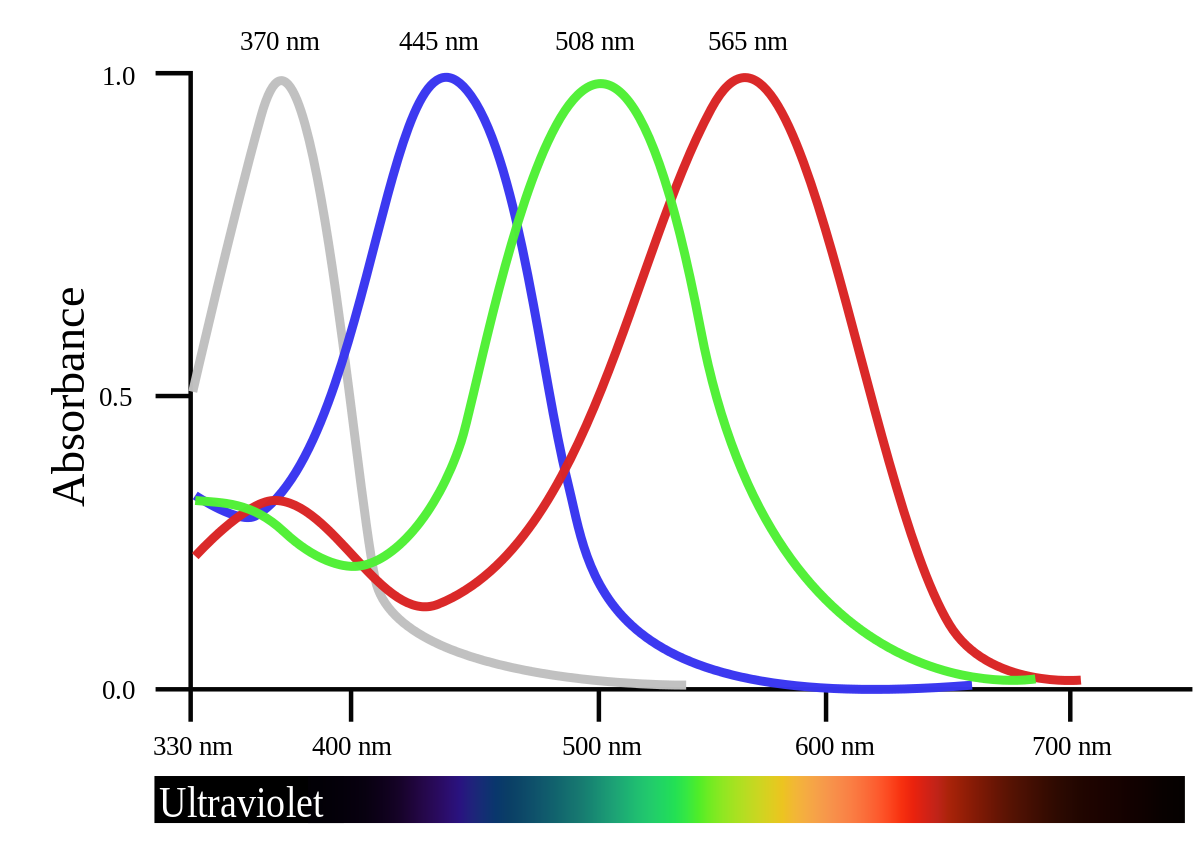

The actual conversion of light into electrical impulse is done by photoreceptors, or rod and cone cells. Rods work on low levels of light, are found on the peripherals of our vision, and are responsible for detecting general movement/changes (very helpful in the dark). Cones work at high levels of light, are found in the center of the eye, and are responsible for visual sharpness and color vision.

To account for the color inputs, there are three types of cones: long (for yellow) medium (for green) and short (for violet). While the existence of the specialized cells is agreed upon, the way in which we reconcile these three colors in our heads is still hotly debated. Also—7% of males have red/green colorblindness because the genes for long and medium cones is on the X Chromosome (more on this in the Sex section).

Both rods and cones have a synaptic terminal on one end, and a strange outer segment filled with Discs. These discs are home to rhodopsin, a critical component to know about for phototransduction. Phototransduction is hard, and so photoreceptors use 10 times the energy that other cells use—that’s why after a long day your eyes start to hurt. Hope they don’t hurt right now!

Phototransduction is unique in that light actually hyperpolarizes photoreceptors, and darkness depolarizes. The resting potential of a photoreceptor is -35mV, which is very depolarized compared to the resting potential of ‘normal’ neurons. This is smart because photoreceptors can therefore “communicate” (change its membrane potential) in two directions: brightness and darkness. Each photoreceptor responds to the lightness/darkness found only a tiny portion of the entire visual field, called their receptive field.

The actual chemical events that cause phototransduction are as follows:

- A photo hits the rhodopsin in a photoreceptor’s discs. The typically U-shaped rhodopsin straightens, and this straightening-out transforms rhodopsin into an activated rhodopsin

- The activated rhodopsin activated about 500 different G-protein molecules, each of which actives a phosphodiesterase, or PDE enzyme.

- PDE molecules rapidly break down nearby cGMP at a rate of 4000/sec. The rapid decline of cGMP causes cGMP-gated Na+ channels to close, and the photoreceptor hyperpolarizes.

Lateral Inhibition

Now we have a hyperpolarized cell, but we still have a few steps until we generate an action potential. Recall the structure of the retina, as it is crucial for understanding this section. As we said earlier, photoreceptors (rods and cones) are hyperpolarized by light and depolarized by darkness. This means that when they are unstimulated (in the dark), they are releasing a steady stream of glutamate into nearby cells, and “turn off” when light shines on them.

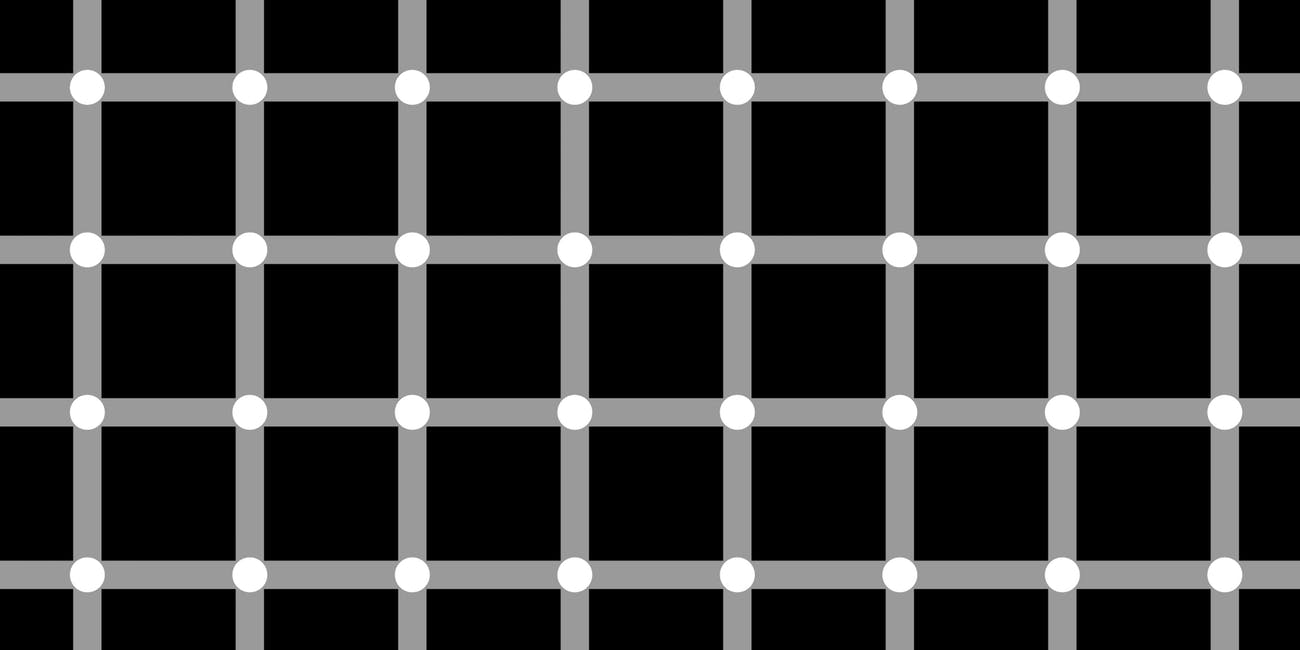

Between the photoreceptors and the bipolar cells are a layer of cells called horizontal cells that connect photoreceptors to other nearby photoreceptors. If you think of the retina pathway as a vertical line, the name horizontal cell makes a lot of sense, as they pass inputs horizontally rather than up-down. Horizontal cells exhibit Lateral Inhibition (discussed previously) by releasing GABA onto nearby cones whenever the cone they are connected to is turned on, essentially turning off the neighboring cones. This is called the center vs. surround receptive field: a fancy name for a system where either (1) the center photoreceptor turns off all the surrounding photoreceptors OR (2) all the surrounding photoreceptors turn off the center photoreceptor. This structure helps the visual system detect edges more accurately.

This center/surround receptive field is passed onto the bipolar and ganglion cells and eventually transferred into the action potentials sent down the optic nerve.

tl,dr; Our senses of…

- Touch & pain are electrical signals created from outside pressure on the body through a process called Transduction

- Sound is when sound waves vibrate our ear hairs which fire action potentials

- Balance comes from fluid in our ears moving ear hairs around

- Taste is a chemical reaction from taste buds on our tongue

- Smell is a chemical reaction from odorant receptors in our nose

- Sight is a neural network of neurons that individually fire based on a simple, single attribute (like orientation)