Your Brain on Drugs

I typed up my behavioral neuroscience notes from college and tried to make the more entertaining. This is more for housekeeping & testing out my blog hosting software than content but… enjoy!

tldr at the bottom

Before we can understand how drugs effect the brain, we need to understand neurons.

Membrane Potential: How Neurons Work

Neurons communicate by sending signals to each other called Action Potentials. To understand how action potentials work, we need to discuss few fundamental concepts of physics/chemistry

Diffusion of Ions

Diffusion is the movement of a substance from high concentration to low concentration. Image food coloring being dropped into water—it slowly starts to spread out from area of high concentration (lots of food coloring) to areas with low concentration (no food coloring) until it is evenly distributed. When an ion, or charged particle, diffuses, something extra happens. As the charged particle spreads out to areas of low concentration, it starts to create a charge in these new areas. This new charge creates prevents new, similarly charged particles from entering. In a sense, it is diffusion for electricity/charge.

For example, Sodium (Na+) has a positive charge. Imagine a high concentration of Na+ floating around a cell that has no Na+ inside it whatsoever (very low concentration). The moment that cell “allows” Na+ to enter, there is a HUGE rush of Na+ from the outside due to diffusion. As this flow occurs, the new positively-charged Na+ ions have given the cell an overall positive charge now. Remember: In electricity, similar charges repel each other. So, the positive charged cell starts to repel the Na+ outside the cell, and it gets harder and harder for new Na+ to rush inside. This is different than in the food coloring example, where diffusion will only stops once all areas have EQUAL concentrations—the charged particles make it so diffusion will stop prior to this point, leaving the cell with a slightly lower concentration of Na+ than the outside.

Eventually the cell and outside Na+ reach a ceasefire, where the pressure from the eq is too strong and the difference in diffusion is too low for any Na+to make it inside. To some up with fancier language: The efflux of Na+ due to positive voltage equals the influx of Na+ due to concentration gradient.

This ceasefire, or when the pressure of Na+ inside the cell due to the positive charge equals the strength of the Na+ outside wanting to diffuse, is called the Equilibrium Potential, and it is a fundamental way that neuron communication works.

Equilibrium Potential & Relative Permeability At Equilibrium Potential, the cell has a charge from all the ions that flooded inside. You can calculate the Equilibrium Potential for each ion with the Nernst Equation:

$$ E=58mv∗log(\frac{ConcentrationOutside}{ConcentrationInside}) $$ For the math inclined, you can see that if the concentration inside and outside was the same, the charge would be 0, because the $log(1) = 0$. But that is never the case due to the voltage within the cell

Equilibrium Potentials for different ions found in neurons:

- Sodium (

Na+) = +50mV - Potassium (

K+) = -80mV - Chlorine (

Cl-) = -80mV - Calcium (

Ca++) = +134mV

A neuron’s membrane potential is the equilibrium potential of the entire neuron taking into account all these ions’ individual equilibrium potentials. The resting potential, or membrane potential when the neuron is not firing, is about -70mV.

It is important to know that neurons have a thick membrane called the Phospholipid Bilayer that prevents pretty much anything from getting inside. Only when special, chemical-specific gates are opened can any ions get inside and diffusion take place. The controlling of what materials enter/leave the cell is called Relative Permeability.

**Sodium (Na+) is the most important compound when it comes to our neurons communicating—it is key to triggering action potentials. To get inside the cell, Na+ has to pass through Sodium Channels. These channels are voltage-gated, which means they only “turn on” when the neuron reaches a certain voltage level. This is crucial to understanding how neurons control the flow of Na+ into the axon.

Action Potentials

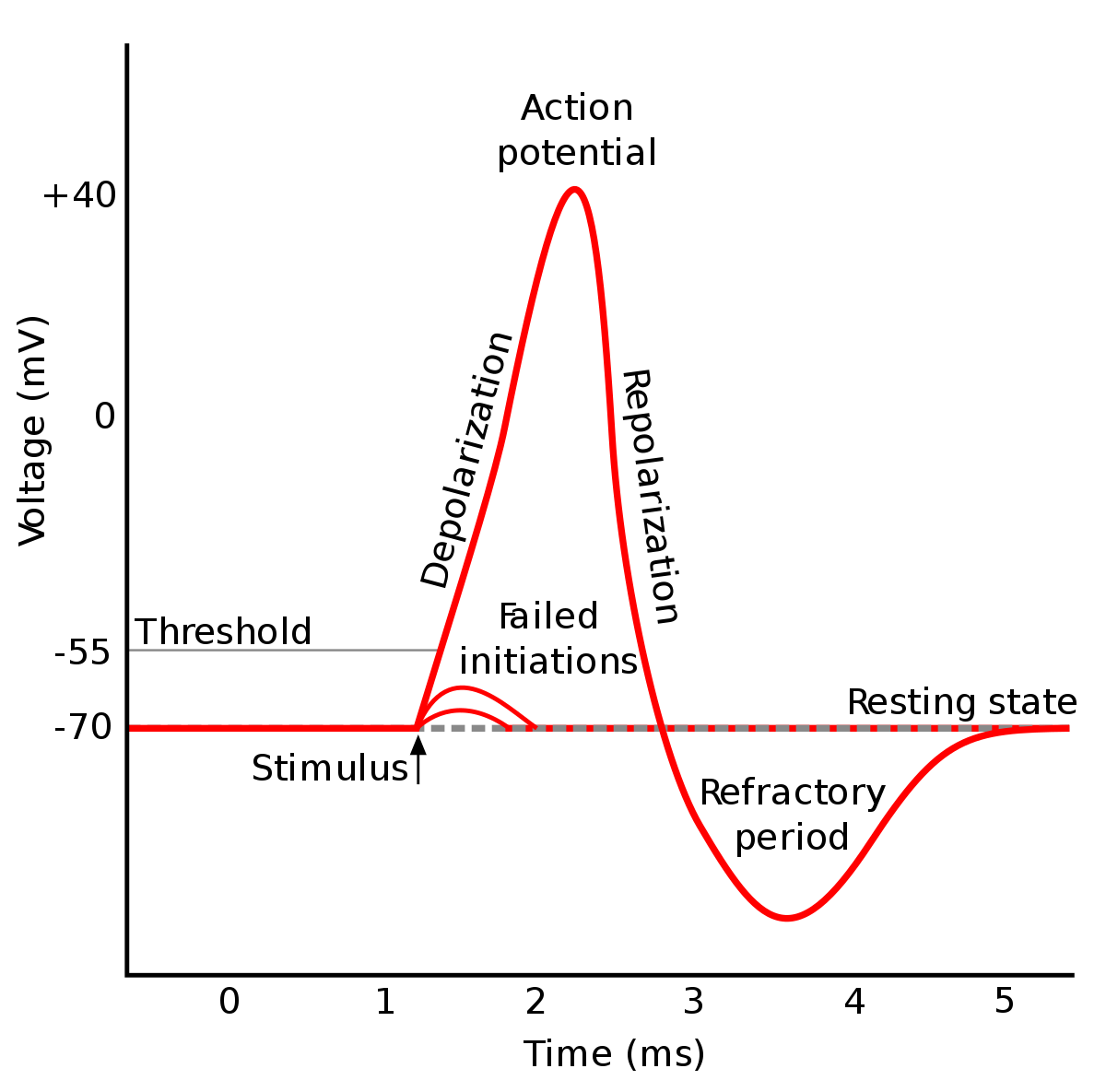

Prior to an action potential, a neuron is at resting potential. It then receives a signal from a nearby cell, which causes the cell to depolarize, or gain a positive charge, ever so slightly. This slight depolarization causes a tiny amount of voltage-gated sodium channels to open, which allows more Na+ ions inside, which causes the cell to depolarize even more. Neurons work on an All-or-None Activation, where the neuron either fully triggers an action potential, or doesn’t fire at all—there is not stronger or weaker neuron action potential. What causes a full action potential is if the depolarization from a nearby action potential pushes the cell above the Threshold. The Threshold, also called the Trigger Event, is the point at which as the cell becomes more depolarized, more sodium channels open, allowing more Na+ to enter, causing the cell to depolarize even further. This Domino Effect of depolarization-Sodium Channels-Na+ influx-depolarization pushes the membrane potential very quickly to the Na+ Equilibrium Potential of +50mV—Sodium overwhelms the neuron.

Incoming signals come in two forms: EPSPs and IPSPs. Excitatory Post-synaptic Potentials (EPSPs) open sodium channels and depolarize the cell, causing “bumps” in the membrane potential. It takes several EPSPs to push the membrane potential over the threshold. This can be done through either Temporal Summation, or multiple EPSPs in rapid succession of each other, or Spatial Summation, multiple EPSPs from different neighboring neurons. Inhibitory Post-synaptic Potentials (IPSPs) open potassium or chlorine channels and hyperpolarize– to gain more negative charge. IPSPs make EPSPs and depolarizations less effective.

Refractory Period

After the peak of the action potential, the membrane potential begins to polarize again towards the resting potential. This is caused by several things:

- After long periods of being active, sodium channels naturally start to get tired and turn off, restricting

Na+ability to depolarize the cell and lower the membrane potential. - As more sodium channels turn off due to inactivity and

Na+begins to leave the cell, even more sodium channels turn off due to the neuron no longer be depolarized enough for them to function - Potassium channels are also activated by depolarization but are slower to open the sodium channels. This influx of

K+ions (which has an Equilibrium Potential of -80mV) continues to push the overall voltage down, causing even more sodium channels to close

The combination of sodium channels closing and potassium channels opening/closing slower causes a huge crash in membrane potential, resulting in a voltage even lower than resting potential. The lower voltage, along with the “exhausted” sodium channels, makes it impossible for the neuron to fire again for a short period of 1 – 2ms. This is called the Refractory Period. After a short refractory period, the neuron returns to resting potential

It is interesting to note natural toxins/poisons cause problems with sodium channels. Saxitoxin found in Pufferfish prevents sodium channels from opening up in the first place, and Batrachotoxin found in Dart Frogs prevents sodium channels from closing.

An additional way that a neuron recovers from an action potential is the Sodium-Potassium Pump, where the neuron takes in more K+ ions and flushes out Na+ ions to return to resting potential quicker

Conduction

While we have seen how a neuron depolarizes and then repolarizes, we haven’t discussed how action potential travel to synapses to transmit a signal to other neurons.

The rapid change in membrane potential creates and electrical charge. This charge then travels up the axon from the cell body to the synapses. This is done through conduction, in which the Na+ ions that rush in during an action potential depolarize the forward-neighboring patch of axon and cause an action potential to arise there as well. The entering Na+ fails to excite backward patches of the axon, and continues to push the electrical charge forward, because it is in a refractory state.

We said previously that myelin helps signal fire quicker, and that is because it reduces the capacitance, or how much charge is required to change the membrane potential. By wrapping sections of axon in myelin fat, entire sections of axon can be depolarized with only a few Na+ ions. This makes depolarization require less ions, less energy (less ions to remove afterwards), and quicker depolarization. The un-myelinated sections of axons where ions diffuse into the neuron are called Nodes of Ranvier.

Synapses & Receptors

When the action potential reaches the synaptic terminal at the end of the axon, it opens voltage-gated calcium (Ca++) channels. The entering Ca++ triggers the activation of synaptic vesicles, bubbles that are filled with thousands of neurotransmitters. These transmitters are then released into the synaptic cleft. As they cross the cleft and reach the neighboring neuron’s dendrites, it binds to nearby receptors, triggering either an EPSP or an IPSP. The neurotransmitters left in the synaptic cleft are cleared away by glia cells, reabsorbed by the synapse, or deteriorate in the synaptic cleft.

There are two kinds of receptors. Ionotropic Receptors are both receptors and ion channels, and therefore result in a fast reaction to the neurotransmitter. Metabotropic receptors are receptors that can activate a G-Protein, which then can then open an ion channel. Metabotropic receptors have a much slower response rate than ionotropic receptors. Studying receptors is quite an active area of research, as it was only recently that we learned that there is a large variety of receptors that can change synaptic behavior.

Ligands are objects that bind to receptors to activate or block ion channels.

- Endogenous: Neurotransmitters and Hormones

- Exogenous: Drugs and toxins from outside the body

- Agonist: Ligand that binds to receptors and opens an ion channel

- Antagonist: Ligand that bins to receptors and blocks the opening of a channel

- Competitive: Ligand that prevents the opening of a channel by blocking an agonist’s binding site

- Non-competitive: Ligand that binds to a different binding site, but still prevents the opening of a channel

Psychopharmacology: How Drugs affect the Brain

Pharmacology is the attempt to influence biological systems (and their disorders) with drugs, and so psychopharmacology is the attempt to assuage problems found in mental systems with drugs. We will first discuss the different compounds and pathways present in the brain, and then talk about the effects common drugs have on these pathways.

Common Neurotransmitters

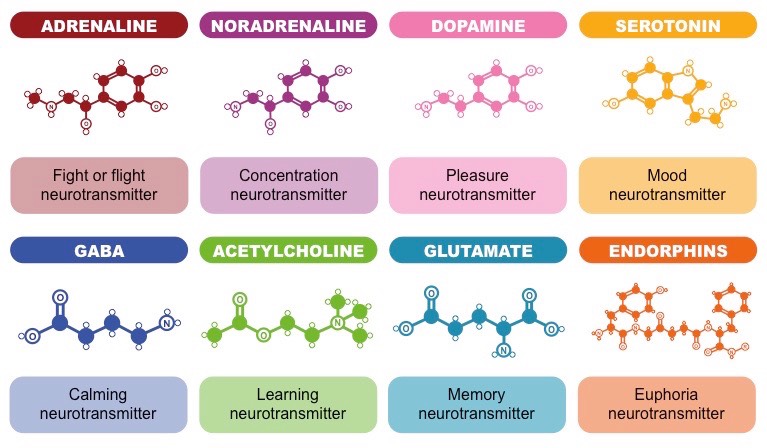

Acetylcholine (ACH) is integral to the “rest and digest” response in the Parasympathetic Nervous System. Triggers actions such as the slowing of heart rate and increased intestinal/gland activity. Found in the chologinergic pathway of the brain involving the cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum. An imbalance in ACH levels has been linked to Alzheimer’s Disease.

Dopamine (DA) is involved in our reward system and movement. These two functions are quite diverse, and so DA emerges from two different pathways in the brain: the DA movement pathway found in the substantia nigra and basal ganglia, and the DA reward system pathway passing through the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the limbic system. A surplus of DA has been linked to schizophrenia, and a scarcity of DA is linked to Parkinson’s Disease. Due to its close relation with the reward system, large dopaminergic responses to a drug/stimulus/behavior is often a major sign of addiction.

Norepinephrine (NA) is responsible for our mood, behavior, sexual impulses, and anxiety. Found in the noradrenergic pathways originating in the brain stem.

Serotonin (5HT) is involved in regulating sleep, mood, sex impulses, and anxiety. Because of its diverse functionality, it is found throughout the brain. The term monoaminic transmitter or monoamine typically refers to DA, NA, and 5HT.

Glutamate is the most common excitatory neurotransmitter. The most common glutamate receptors are AMPA, Kainate, and NMDA receptors. GABA is the most common inhibitory neurotransmitter. The most common GABA receptors are GABA-A, GABA-B, and GABA-C (creative names).

Drugs

Antidepressants work by accumulating monoamines and prolonging their activity. There are three kinds of antidepressants:

- Monoaminic oxidase inhibitors (MOAIs) work by preventing the breakdown of monoamines, increasing the amount found in synaptic vesicles

- Tricyclic Antidepressants block the reuptake of NA and 5HT, increasing the amount available

- Selective Serotonin Receptor Inhibitors (SSRIs) allow 5HT to accumulate in synapses. This is the currently the most common form of antidepressant—Prozac and Zoloft are SSRIs

Amphetamines boost the excitatory effects of neurotransmitters by blocking reuptake:

- Cocaine blocks monoaminc transporter proteins and slows reuptake, increasing their effects. This blocking causes the degradation enzyme to reduce in effectiveness even after the immediate high has worn off.

- Caffeine blocks adenosine receptors, a neurotransmitter that makes you sleepy. Interestingly it is both an antagonist because it blocks adenosine and also an agonist by allowing normal transmitters to continue.

Alcohol depresses and lower inhibitions by activating GABA-A receptors. It also depresses activity in the cerebellum (motor coordination) and the dopaminergic pathway (stimulation and reward).

Opiates typically reduce the emotional response to pain by mimicking proteins such as endorphins and dynorphins. Endorphins are released when you exert excess energy, and are the cause of the “runner’s high” people get when exercising.

Hallucinogens often influence our interpretations of sensations, and effect synapse efficiency even after “trip” is over:

- PCP and Ketamine are antagonists for NMDA receptors and stimulate DA release.

- LSD and Psilocybin stimulate excess 5HT release. MDMA increases 5HT levels and triggers DA release as well.

- Marijuana modulates glutamate release.

Nicotine is an agonist for ACH in the reward system. This increases heart rate and blood pressure, and the ability to take multiple short hits in rapid succession makes it addictive.

Tolerance, or the lack of effectiveness of a substance after prolonged use, is a common attribute of drug use. There are multiple kinds of tolerances. Drug Tolerance is the most straight forward, in which each successive treatment has a decreasing effect. Metabolic Tolerance is when the liver becomes better at inactivating/eliminating the drug. Functional Tolerance is when the target tissue responds to treatment and reduces sensitivity—either Down-regulating, decreasing number of receptors in response to an agonist, or Up-regulating, increasing the number of receptors in response to an antagonist. Cross-Tolerance is when tolerance of a chemically similar drug decreases the effectiveness of a treatment. Addiction is often caused by a dopaminergic response in the reward system.

tl,dr;

- Neurons fire because the diffusion of positively-charged sodium into the cell causes an electrical charge to travel up the axon

- Diffusion is when an object moves from high concentration to low concentraion (this is how electric currents work too)

- Psychopharmacology is using drugs to treat mental system problems

- Drugs work by affecting how these neurotransmitters are produced, released, or broken down