Behavioral Neuroscience IX

How do we See Things?

The visual system is so important, and so complicated, that I’ve broken it into two sections: how the eyes transform light into brain signals, and how our brains interpret those brain signals. Get ready for a crazy ride.

The Eye: How we See Things

The colorful part of your eye is called the iris. When light first enters the eye, it passes through the donut hole in the middle of your iris called the pupil- which really is a hole leading inside your eye. Light then passes through your cornea and lens. Your lens controls your focus—when you relax the muscles around eye your lens flattens, allowing you to focus on distant objects. The lens also inverts the incoming lights so that the image that hits the back of your eye is upside down. All vertebrate eyes invert the incoming light in this way.

The light then hits the retina in the back of the eye, where the light is changed into action potentials by vision cells and sent down the optic nerve. But changing light into electric impulses, as you can imagine, is a very involved process.

A quick not about eye movement—our eyes saccade, or jump, 3-4 times a second. Vision is not a continuous movement, but rather a series of ¼ second glimpses. Watch someone look from left to right, their eyes will make a series of short jumps! We can only move our eyes smoothly when following when tracking a moving object.

The Retina

The basic anatomy and order of the retina, for reference later, is:

- Rods/Cones

- Bipolar Cells

- Ganglion Cells

- Optic Nerve

We will slowly walk through each of these layers, but make sure you have a clear picture in your head about all the retina structures as you go along. What you should also know before you begin is that despite being the 3rd layer of vision cells, the ganglion cells are the vision cells that actually fire action potentials.

The first thing light hits when it reaches the back of the eye, and before it reaches the first layer of vision cells, is the pigmental epithelium. This is a thin layer of cells that absorbs unused light.

At the center of the retina is the fovea. The fovea is a part of the center that pushes away all other layers (like the pigmental epithelium) so cone cells can have direct access to light, unimpeded by blood vessels that typically obscure incoming light. The fovea cones are densely packed, giving the Fovea very high visual resolution—this is why your vision is best when you look straight at something.

Another reason that vision in the fovea is so sharp, and it drops off as we move away from center, it that the cones, bipolar cells, and ganglion cells are hooked up to each other in nearly a 1 to 1 to 1 ratio. With a 1 to 1 to 1 ratio, any small change in the visual field detected by a single cone cell will be communicated to the brain, while a larger ration would be this change would be mixed in with other signals being processed.

We have about 125 million photoreceptors in our retina, with nearly 100 million of those being rods and the rest being cones. Despite having over 100 million photoreceptors, all these inputs have to be compressed down to fit into 1 million ganglion cells. This difference in magnitude is the reason why having a 1 to 1 to 1 ratio in the fovea is really impressive and important, and why our vision on the peripheries drops off considerably as we move away from the center of the eye.

We can typically see between 400 – 700 nm, which means we can anything smaller than that we can’t see fine details. The term 20/20 is an ophthalmology (eye doctor) term stating how acute your vision is in comparison to normal. If you have 20/40 vision, that means you see at 20 feet as most people see at 40 feet.

The Retina is also home to the Optic Disc, where both blood vessels and ganglion cell axons can enter/leave the eye. While blood flow and neural connectivity are important, this comes at the cost of having a portion of the retina with no photoreceptors. This creates a blind spot, a blank spot in our visual field. You don’t notice this blind spot because your brain fills in the empty space with what it guesses is around it! There are plenty of quick tests you can find online that help you find your blind spot, it’s pretty awesome.

Photoreceptors & Phototransduction

The actual conversion of light into electrical impulse is done by photoreceptors, or rod and cone cells. Rods work on low levels of light, are found on the peripherals of our vision, and are responsible for detecting general movement/changes (very helpful in the dark). Cones work at high levels of light, are found in the center of the eye, and are responsible for visual sharpness and color vision.

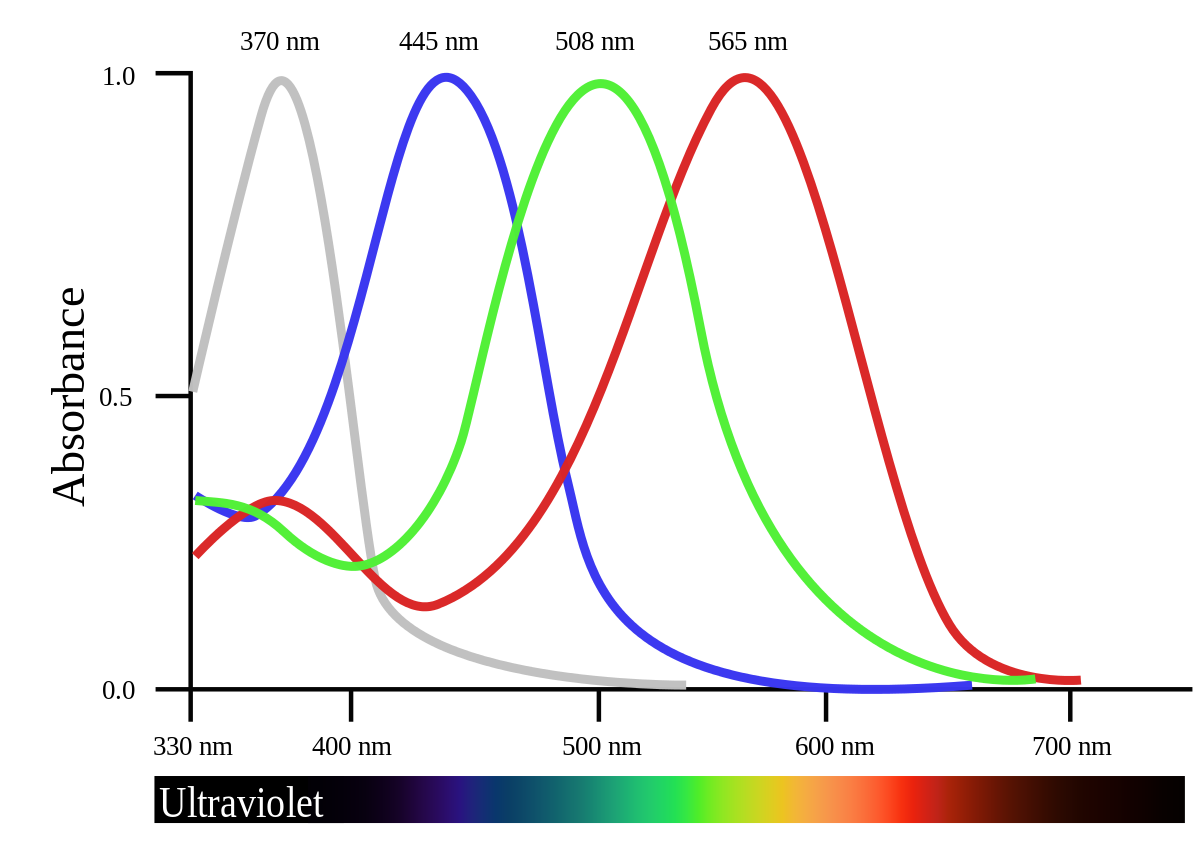

To account for the color inputs, there are three types of cones: long (for yellow) medium (for green) and short (for violet). While the existence of the specialized cells is agreed upon, the way in which we reconcile these three colors in our heads is still hotly debated. Also—7% of males have red/green colorblindness because the genes for long and medium cones is on the X Chromosome (more on this in the Sex section).

Both rods and cones have a synaptic terminal on one end, and a strange outer segment filled with Discs. These discs are home to rhodopsin, a critical component to know about for phototransduction. Phototransduction is hard, and so photoreceptors use 10 times the energy that other cells use—that’s why after a long day your eyes start to hurt. Hope they don’t hurt right now!

Phototransduction is unique in that light actually hyperpolarizes photoreceptors, and darkness depolarizes. The resting potential of a photoreceptor is -35mV, which is very depolarized compared to the resting potential of ‘normal’ neurons. This is smart because photoreceptors can therefore “communicate” (change its membrane potential) in two directions: brightness and darkness. Each photoreceptor responds to the lightness/darkness found only a tiny portion of the entire visual field, called their receptive field.

The actual chemical events that cause phototransduction are as follows:

- A photo hits the rhodopsin in a photoreceptor’s discs. The typically U-shaped rhodopsin straightens, and this straightening-out transforms rhodopsin into an activated rhodopsin

- The activated rhodopsin activated about 500 different G-protein molecules, each of which actives a phosphodiesterase, or PDE enzyme.

- PDE molecules rapidly break down nearby cGMP at a rate of 4000/sec. The rapid decline of cGMP causes cGMP-gated Na+ channels to close, and the photoreceptor hyperpolarizes.

Lateral Inhibition

Now we have a hyperpolarized cell, but we still have a few steps until we generate an action potential. Recall the structure of the retina, as it is crucial for understanding this section. As we said earlier, photoreceptors (rods and cones) are hyperpolarized by light and depolarized by darkness. This means that when they are unstimulated (in the dark), they are releasing a steady stream of glutamate into nearby cells, and “turn off” when light shines on them.

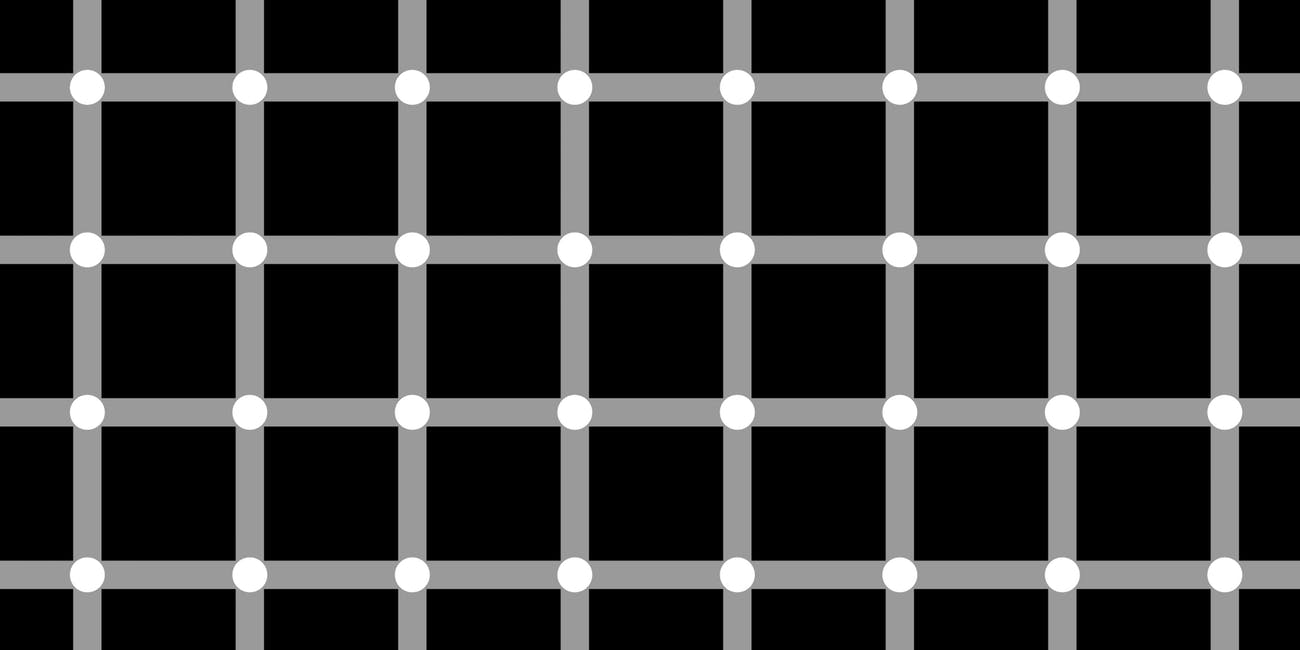

Between the photoreceptors and the bipolar cells are a layer of cells called horizontal cells that connect photoreceptors to other nearby photoreceptors. If you think of the retina pathway as a vertical line, the name horizontal cell makes a lot of sense, as they pass inputs horizontally rather than up-down. Horizontal cells exhibit Lateral Inhibition (discussed previously) by releasing GABA onto nearby cones whenever the cone they are connected to is turned on, essentially turning off the neighboring cones. This is called the center vs. surround receptive field: a fancy name for a system where either (1) the center photoreceptor turns off all the surrounding photoreceptors OR (2) all the surrounding photoreceptors turn off the center photoreceptor. This structure helps the visual system detect edges more accurately.

This center/surround receptive field is passed onto the bipolar and ganglion cells and eventually transferred into the action potentials sent down the optic nerve.

Recap

- We see when light passes to the back of our eye, where it causes a chemical change in the cells of the retina. This chemical change leads to an action potential

- Our eye has unique properties in comparison to other senses to increase its ability to sense finer details about our world, like lumosity and edges

Visual System: How we See Things

The goal of our visual system is to create a 3D representation of the world from 2D retinal images. Not an easy task. The good news is that I think vision scientists have the best/laziest names for brain structures we have seen so far, like “Blob” and “simple cell”…

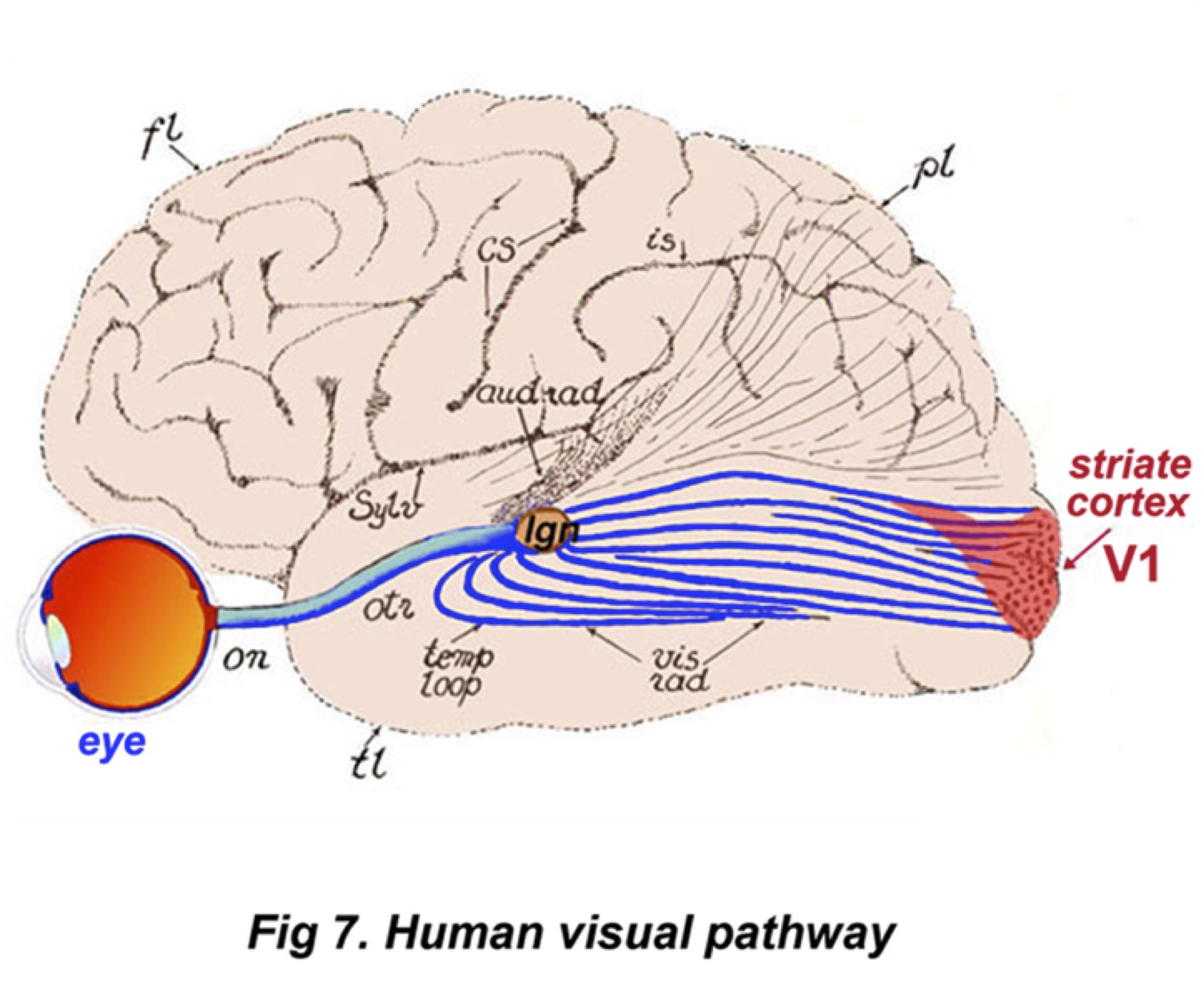

LGN

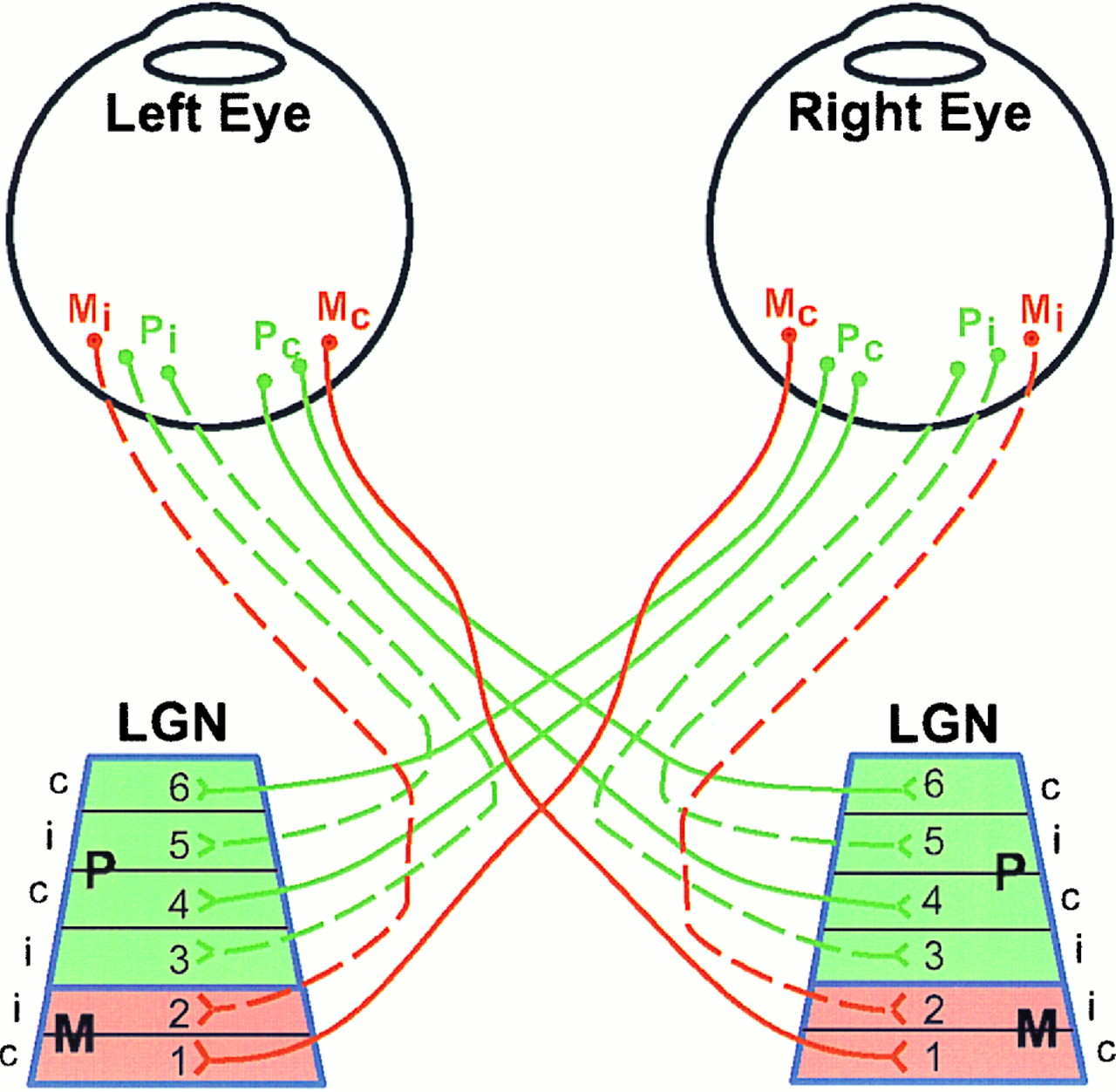

First, remember that we process information from the right side of our body in the left side of our brain, and information from the left side of our body in the left side of our brain. The same is true for our eyes, and so the input into the optic nerve is crossed before it reaches its first destination within the brain—which is the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus (LGN). The LGN is a relay pathway in the Thalamus specifically designed for visual stimulus; any sensory information that enters consciousness passes through here (reflex-related stimuli are directed elsewhere). It contains two types of cells: parvocellular (P cells) and magnocellular (M cells). P cells are small with about one P cell for every retinal ganglion cells, meaning P cells maintain the center/surround field. Because of this replication of ganglion cells, P cells are slow to change firing rates. M cells have a large receptive field, taking in the inputs of many P cells and rapidly adapting their firing rate to changing stimulus. There are around 100,000 per eye, a relatively small number when compared to how many P cell and ganglion cell inputs M cells are receiving.

The LGN has 6 layers, with 4 of those layers containing P cells and 2 containing M cells. Between layers 2-3 and 3-4 there are color detectors called koniocellular cells. The reason for these layers is to utilize parallel processing, or the ability to analyze multiple things are the same time, as well as for verifying quality and topography of a visual stimulus. As you will see, the visual system often feeds the visual input back onto itself to reanalyze after learning some additional information.

V1

V1 brain region is the primary visual cortex, located in the back of the head. It receives input from multiple layers of the LGN and is made up simple cells, complex cells, and hypercomplex cells. Simple cells are sensitive to orientation, and only respond when a stimulus has a particular stripe in the correct orientation. This means that a perfectly straight line may activate a certain simple cell, but a diagonal line in the same place will not. In the context of vision, these “lines” typically mean edges between lighter and darker areas of the visual field; in addition. Complex cells take in a combination of simple cell inputs, building up a hierarchy of cells. Hypercomplex cells do the same thing as complex cells, only they stop firing if a stimulus continues for so long. The ‘message’ from a single cell is ambiguous, since the firing rate.

The closer the detected “line” is to the simple cell’s preference, the more times the cell will fire. But other factors effect firing rate as well: contrast, thickness, color, speed, etc. Since the ‘message’ from a single cell is ambiguous, the visual system has to extract orientation by comparing firing rates of cells with different orientation preferences and figure out which cell has the peak firing rate. Primates evolved to solve this problem by developing structures called The Ice Cube Model. The Ice Cube Model is made up of columns of simple cells, each column of cells preferring the same orientation. The columns are further chopped into rows, where the rows relate to the cell’s ocular dominance, or which eye’s input they care about more. It’s called the Ice Cube Model because the simple cells are chopped into blocks and stacked together, like ice cubes in a tray. This continuous and fine-grain mapping of orientation permits a systematic survey of firing rates for different orientations, and helps the brain figure out the actual orientation. Amazing!

Blobs are blocks of cells in the cortex, about .5mm by .5mm, that are theorized to process color. These blobs are made up of cells that all fire in the same orientation but are selective for color. There are about 10,000 modules, and there is more than one module for the central gaze. Form, color, and motion all pass through the LGN, V1, and blobs during processing.

Beyond V1 there are over 30+ visual areas visual signals go, collectively called the Extrastriata visual cortex, which just means “others areas that also process vision.” V1, along with other areas, continues to feedback into LGN and onto themselves for parallel processing. As we move further down the visual system pathway, the quality of understanding increases. There are two main vision pathways, the dorsal steam and the ventral stream. The Doral Stream is the “where” pathway, which helps us place objects in position around of visual field. Damage to this pathway causes Optic Ataxia, or difficulty using vision to reach of an object. The Ventral Stream is the “what” pathway, helping with identifying objects .

Recap:

- The LGN and V1 receive the input from the retina, and process the information by comparing the firing rates of all of their cells, arranged in blocks and blobs

- The cells in the most important areas of the visual system respond to orientation.